Impressions from a Lost World: The Discovery of Dinosaur Footprints

Theater in 19th Century New England

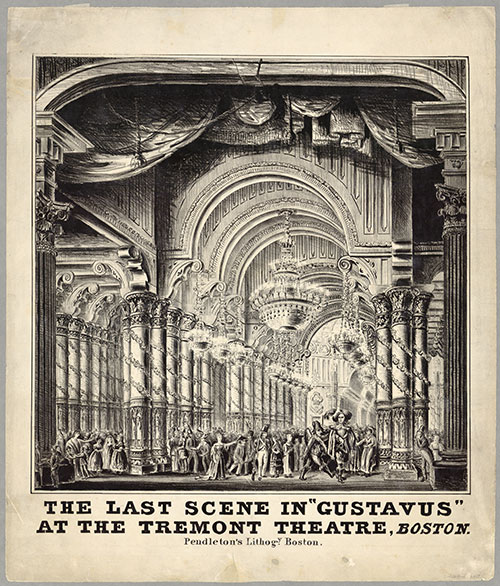

Image courtesy of American Antiquarian Society.

Theater and theatrical performances in general became increasingly common in New England during the early 19th century. Although more common in larger towns like Boston, surviving playbills, diaries and correspondence are evidence of a thriving interest in plays and acting among amateur as well as professional performers. At the same time, there was deep-seated ambivalence about the possible bad effects of theater, especially upon young, impressionable minds. In 1824, Timothy Dwight, a former president of Yale College, warned that “to indulge a taste for play-going means nothing more or less than the loss of that most valuable treasure the immortal soul.”

For many, their concerns were in part an inherited hostility to traditional forms of popular entertainment from their Puritan forebears. Elizabethan England had developed a vibrant and lively theater, thanks to William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and many lesser known playwrights and actors. English Puritans, however, believed theaters turned patrons away from spiritual matters and encouraged vices that included excessive drinking and lewd behavior. Sometimes referred to by Patrick Collinson and other historians as a “hotter sort of Protestant”, Puritans had an antipathy to play acting along with other forms of public entertainment such as bear baiting, Maypole celebrations, Morris dancing and other village entertainments. When Puritan factions gained control of Parliament during the English Civil War, they promptly closed down all the theaters in the country. In 1644, they demolished the Globe Theater in London, famous for having been the home of William Shakespeare’s theater company, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

The Puritan hostility to theater explained Massachusetts laws like the statute the General Court passed in 1750, banning stage or theatrical entertainments of any sort. At the same time, there is plenty of evidence that performances did take place, and that this activity increased as the 18th century wore on. This was partly due to the quality of the plays being written and partly to their appeal to American audiences. For example, Joseph Addison’s Cato, a Tragedy, was extremely popular in the colonies. His plot revolved around the final days of Cato, a Roman citizen valiantly fighting to save the Roman Republic from the rise of Julius Caesar. The play’s stirring speeches defending freedom and condemning tyranny made Cato a literary inspiration for many American patriots. George Washington carried a copy of the play with him during the war and may have had it performed at Valley Forge.

A growing consensus suggests there was little or no reluctance among educated people about theater, either professional or amateur, so long as the subject matter was educational and encouraged moral reflection. As a young preceptor (headmaster) of Deerfield Academy, Edward Hitchcock wrote a play in his youth that focused on the fate of Napoleon Bonaparte. Published in 1815, Emancipation of Europe: Or, Downfall of Napoleon met with universal approval, although Hitchcock later regretted having published it, not because it was a play but because he was embarrassed by what he considered its callow immaturity. Academy classes on rhetoric and elocution flowed easily into plays and other amateur theatricals. Not all of these were serious and some poked fun. An academy in Greenfield, Massachusetts, included in its end-of-term exercises a sparkling parody. In one scene, a young woman worried about the potential side effects of an academy education on the boys in her town, exclaiming, “How will the young fellows take it if we shine away & don’t like their humdrum ways—Won’t they be as mad as vengeance—& associate with the girls that don’t go to school?”

Tyrone Power, a well-spoken Irish actor (and the first of three generations of actors of that name), toured in the States in the early 1830's and shared in Impressions of America that the Bostonian audiences he encountered were reputable and attentive, adding, “Some of the kindest gentlest and the most hospitable friends I had were, as they say here, ‘real Yankee', born and raised within sight of the State-house of Boston." Another famous European traveler who traveled extensively in New England in the 1820's was far less complimentary than Power. According to Alexis de Tocqueville, Puritan hostility to theater had “left deep traces on the minds of their descendants.” He believed these attitudes “have up to now told against the growth of the drama.” As for comedy, “[p]eople who spend every weekday making money and Sunday in praying to God give no scope to the Muse of Comedy.”

Tocqueville’s dreary assessment helps place in context Timothy Dwight’s concerns in 1824, about the effects of plays on the morals and spiritual health of Yale students. The growing presence and popularity of the theater in the same period, however, suggested a bright future for professional and amateur actors, and their audiences.