MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

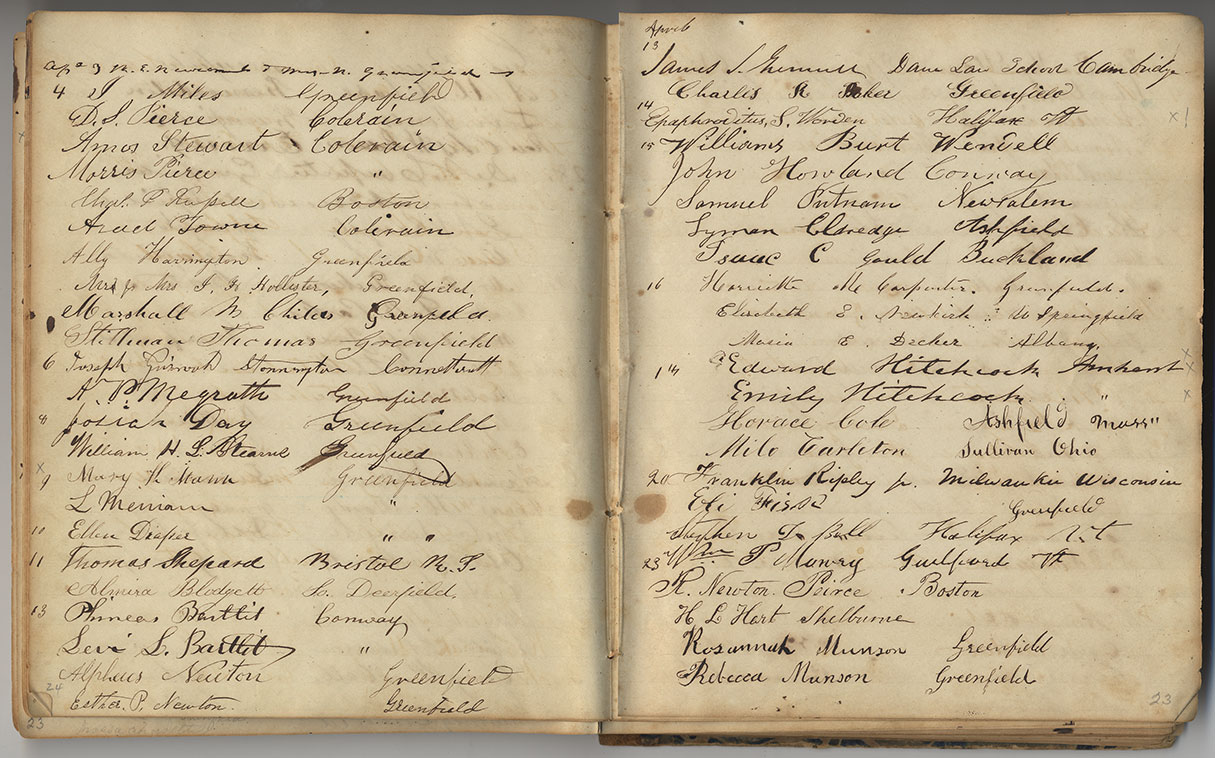

The Visitors Book from Dexter Marsh's Cabinet. The right-hand page shows that Edward and his daughter Emily, then age 8, visited on April 17, 1846. Image courtesy of Dexter Marsh Papers, Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

The "cabinet of curiosities" was a popular way for people to display cultivation and knowledge about the natural world in their homes. A cabinet could be anything from a shelf of seashells to a more elaborate set of shelves or even, for the wealthy, a whole room of interesting objects from nature and relics from past civilizations. Only a handful of museums existed in the way we think of them today, as places where research is done and the general public can view the collections, so Edward Hitchcock’s official opening of the Woods Cabinet at Amherst College in 1848, was a forward-thinking enterprise. Probably aware of Hitchcock's plans, Dexter Marsh built an additional room onto his house and opened it to the public on January 2, 1846.

From then until 1852, the little museum was an attraction in Greenfield. Farmers and factory workers from the hill towns, local shopkeepers, laborers like himself, and the gentry who had hired him to do their chores came to see his room chock-full of fossil "bird tracks," water ripple marks, mud cracks, and other natural items.

Like any true cabinet, Marsh's collection was not restricted to only one type of item. It also included a whale's tooth, corals, shells, snakeskins, fish fossils, Indian arrowheads, even coins: a Scottish visitor noted "an ancient piece of American coin, called the 'Pine-tree Sixpence,' being the first money coined in this country," neatly linking together natural history and patriotic pride.

Visitors from out of town came, too, including well-known scientists and other educated people. The Visitors Book kept by the door includes the signatures of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Amariah Brigham (James Deane's first medical mentor), a teenaged Austin Dickinson (Emily's older brother), and such "scientific men" as Charles Upham Shepard, William Redfield, and members of the Boston Society of Natural History. Visitors from Germany and Poland signed the book, as did American missionaries on a visit home from Turkey. In 1847, a newspaper in Glasgow, Scotland, quoted a letter sent in by a Scottish visitor expressing his astonishment at the fossil footprints in Greenfield.