MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

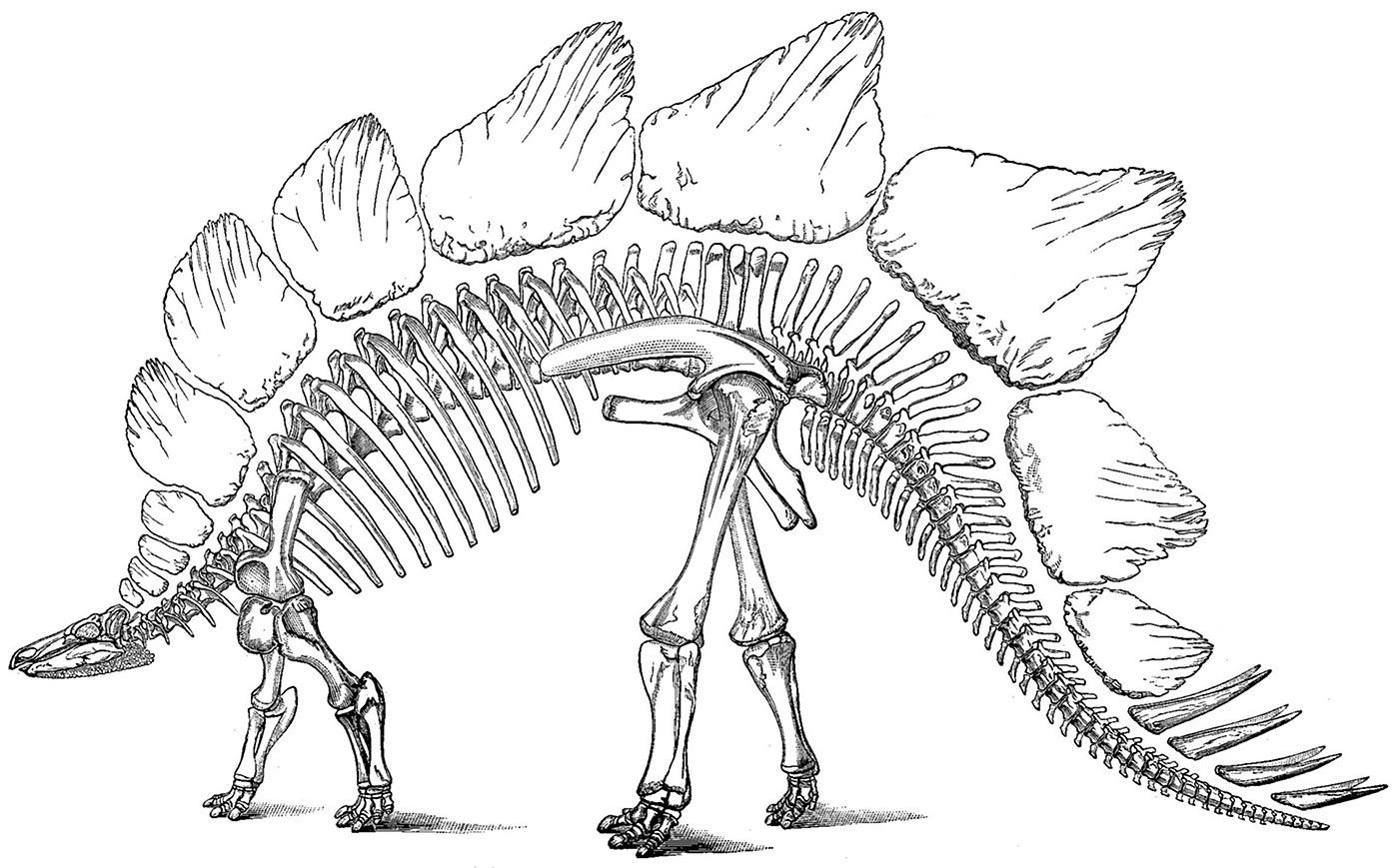

Othniel Charles Marsh's 1896 illustration of the bones of Stegosaurus, a dinosaur he described and named in 1877. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Edward Hitchcock died in February of 1864, just over a year before the end of the Civil War. Studies of local tracks carried on, but preoccupation with the war's urgent concerns drew Americans' interest away from something so far from moral issues and daily life as fossil footprints.

A few years later, an Amherst College graduate named Benjamin Kendall Emerson returned to join the faculty as Professor of Geology, and in addition taught female students at then-new Smith College. Emerson included footprints among his interests but departed from Hitchcock's legacy by teaching his students Darwin's evolutionary ideas.

Fossil footprints were no longer a novelty, but in 1877, interest in dinosaurs was given another boost. Huge bones of dinosaurs discovered in Morrison, Colorado, set off the famous "Bone Wars" between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh (no relation to Dexter Marsh). O. C. Marsh, a giant in the history of dinosaur paleontology, visited Roswell Field and Timothy Stoughton at Gill, Massachusetts, and purchased specimens for the Yale College's Peabody Museum. However, O. C. Marsh's primary interest was in the spectacular skeletons of the American West, and he never delved far into the study of fossil footprints.

In the next generation, Richard Swann Lull took up the study of fossil tracks, teaching briefly at the Massachusetts State Agricultural College, which Hitchcock helped to found, before moving on to Yale.

During the first half of the 20th century, dramatic expeditions in search of dinosaur bones in Mongolia and other places far from American shores gave a heroic image to paleontologists and drew flocks of admirers to gawk at ever-stranger skeletons. Few gave fossil footmarks more than passing notice.

Serious interest in the tracks was revived in the 1960s by Yale's John Ostrom, whose observations at one of Hitchcock's old sites gave him the idea that dinosaurs might have traveled in packs. Some of Ostrom's students became today's leaders in the field of ichnology, and they, in turn, paved the way for a new generation of young paleontologists drawn to the adventure of studying dinosaurs.

Fossil footprints have helped to change paleontologists' vision of dinosaurs as cold-blooded, dull-witted, reptilian animals who went extinct because they lacked the fitness to survive, to today's image of a vast assortment of warm-blooded, fast-moving, birdlike creatures, some of which were wiped out by disasters, while others evolved into modern birds.

Footprints have now been found all over the world, on every continent, even including Antarctica. Not all are like the three-toed tracks of the Connecticut River Valley, generally associated with small to mid-sized dinosaurs. A few examples are Stegosaurus tracks in Colorado, Tyrannosaurus-rex tracks in Bolivia, and Hadrosaur footprints in Alaska.

Paleontologists today still use the basic principles set down by Hitchcock more than a century and a half ago, but years of examination and modern technology and techniques have created new ways of looking at and even thinking about dinosaur footprints.