MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

The correspondence among Hitchcock, Silliman, Deane, Mantell, Lyell, and other geologists in American and England was copious, and individual letters could be quite long. Image courtesy of Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association/Memorial Hall Museum.

Deane was pleased with Roderick Murchison’s remarks, but Hitchcock was not. Was he some lowly drudge, merely filling in the details for Deane, the Great Thinker? Certainly not.

At first, Hitchcock wanted to lay out his argument in the American Journal of Science, but Silliman's lack of enthusiasm moved him to instead make his case at the May 1844 meeting of the Association of American Geologists, this time held in Washington, D.C. There, Hitchcock named himself as discoverer of the fossil footprints and disparaged Deane’s contributions by mentioning several other men who had come across them before Deane had: the farm boy Pliny Moody; Dr. Dwight, who had bought Moody's specimen; and a Mr. Wilson, whom Hitchcock credited with having drawn Dr. Deane’s attention to the tracks in the first place. Hitchcock also made a remark in a letter to Silliman that sounds as if Moody had made his own claim, but the reference is ambiguous and the evidence has not survived.

Upon reading Hitchcock's remarks when they were printed in the American Journal of Science as part of the AAG's meeting records, Deane was “filled with vexation and astonishment". Now, even Mr. Wilson was being given more credit than he, and Mr. Wilson had done nothing!

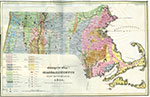

Silliman was in an awkward position. Hitchcock was a dear friend and colleague of long standing, a significant scientist who was no longer Silliman's protégé. Hitchcock was a professor at Amherst College, the first official state geologist for Massachusetts and creator of its first geological map, and had earned a reputation in Britain and Europe for his geological work. Silliman also was aware that Hitchcock had just been asked to become president of Amherst College. It was no longer a mentor-protégé relationship. The men were on much more equal footing.

But Silliman also liked and respected James Deane, to whom he had always felt Hitchcock should have given more credit in his first article on the tracks in 1836. Caught in the middle, Silliman felt honor-bound to mediate as best he could, without taking sides. It was not easy.

Next chapter: The Argument in the American Journal of Science

Elihu Dwight

Elihu Dwight

Pliny Moody

Pliny Moody

William Wilson

William Wilson

A Geological Map of Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock

A Geological Map of Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock

Proceedings of the Association of American Geologists, American Journal of Science, May 1844

Proceedings of the Association of American Geologists, American Journal of Science, May 1844

Edward Hitchcock's Three Letters to James Deane, 1835

Edward Hitchcock's Three Letters to James Deane, 1835

Benjamin Silliman's Letter to Edward Hitchcock, August 6, 1835

Benjamin Silliman's Letter to Edward Hitchcock, August 6, 1835

Charles Darwin's Letter to Edward Hitchcock, November 6, 1845

Charles Darwin's Letter to Edward Hitchcock, November 6, 1845