MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

Loch Lomond reminded the Hitchcocks of Lake George in the Adirondaks of New York State. This view was painted by Gustave Doré, "Souvenir of Loch Lomond", 1875. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Scotland's River Clyde reminded Orra and Edward of the Connecticut River, but with higher mountains and different-looking buildings. On a field trip to Fort William, Orra was impressed by the purported birthplace of the legendary poet Ossian: “Surely if wild & romantic scenery has anything to do with writing poetry, I shall suppose all who inhabit this vale & almost thought all who ride through it, except the stupid ones like myself, must be inspired with a poetic spirit.” She was becoming blasé about travel and a little despondent and homesick. “New scenes do not excite me as much as they did. I have become accustomed to them.”

Home was on Edward’s mind, too. Loch Lomond reminded him of Lake George in New York. Also similar to home, the countryside was barren of trees, the rounded mountains covered in pebbles and coarse sand. In a stream, he discerned evidence of river erosion and mused that similar geological processes must have shaped both landscapes.

En route to Glasgow by train, Orra saw a group of Quakers carrying “mementoes of their tour, minerals, plants, etc.,” so much in keeping with her own habits. She and Edward were permitted to get off the train to observe a schoolroom. Orra thought one student ill-treated for a minor mistake, yet pitied the young teacher overwhelmed by forty or more pupils. In Glasgow, they visited the other Hunterian Museum (related to the one in London) and the churchyard cemetery where the founder of the Presybterian Church of Scotland, John Knox, was buried ("Oh, what a dirty street it is now," said Edward). Edward was intrigued by the types of Presbyterians: Established, United Seceders, and Free Church, this last given its name by the self-taught geologist so admired in America, Hugh Miller.

Nearly ten days after leaving Ireland, slowly making their way east, they arrived in Edinburgh for the week-long conference of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. They stayed at Sinclair’s Temperance Hotel, near Princes Street. Edward disapproved of the many monuments to literary and military men in Edinburgh: even if he admired poets, he disliked the glorification of "unsanctified genius."

At a soiree in the home of the prominent Scottish geologist Robert Jameson, Edward was introduced to a woman of high social standing, in whom he discerned intelligence and capability. He told her how at home he felt in Scotland, describing the similarities to New England in religious views and universal education. Even the geology felt familiar. The lady did not share Hitchcock’s opinion of universal education: “It makes our servants discontented with their condition, and they would be much better without so much knowledge,” she told him. Hitchcock was well aware that without the educational opportunities given him as a poor youth, his life would have been much different and much smaller. He tried to argue, but to no avail.

One of a tiny handful of Americans in attendance at the conference, Edward presented two papers, one on New England terraces and the other on erosion by river action, and was received respectfully by the most important geologists of the day. Here was Edward Hitchcock, representing American geological scientific thinking, surrounded by the cream of British geologists: Roderick Murchison, Gideon Mantell, Hugh Miller, Robert Jameson, and many more. Murchison sought his opinion of glacial action, to which Edward replied that his observations in Wales showed that the mountains there had been shaped by glacial action, a view that, while not novel, was not yet generally accepted.

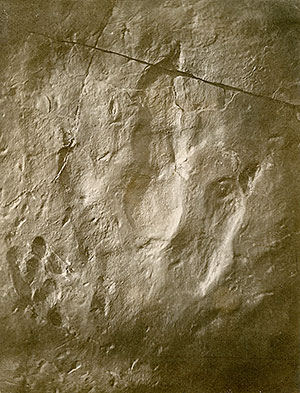

The meeting was large: 894 men, 15 foreigners, and 212 ladies. Women attended the sessions as well as the field trips and evening soirees. Orra did not think much of the ladies’ taste in dress, but supposed that this was because they were intellectual, rather than “fashionable” ladies of the “highest circle.” Edward was pleased to see that 97 clergymen had come, and wished that American clergy would follow their example. A presentation on "Talbottypes" (an early form of photography, also called calotypes) may have influenced him to use ambrotype photographs years later in his final book on fossil footprints. Unfortunately, he said little about the conference except that it did not seem any better than American ones, but it is apparent that whatever lingering insecurities he might have had as an American scientist had at last dropped entirely away.

Listen to what Orra wrote in her travel diary.

Lydia Mackenzie Falconer Miller

Lydia Mackenzie Falconer Miller

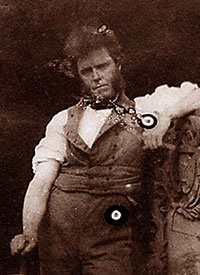

Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller

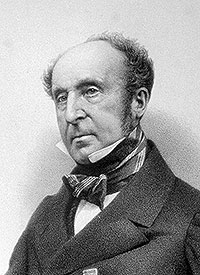

Roderick Impey Murchison

Roderick Impey Murchison

Orra White Hitchcock's Letter to the Children, August 12, 1850

Orra White Hitchcock's Letter to the Children, August 12, 1850

Edward Hitchcock's Papers Presented at Conference in Edinburgh

Edward Hitchcock's Papers Presented at Conference in Edinburgh

Photography and Geology

Photography and Geology

The Parallel Roads of Glen Roy

The Parallel Roads of Glen Roy

British Association for the Advancement of Science

British Association for the Advancement of Science

Edward Hitchcock and Glacial Theory

Edward Hitchcock and Glacial Theory