MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

A surveying tool that Edward used to map the state. Image courtesy of Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association/Memorial Hall Museum.

Edward was a man of contradictions. He paid hypochondriacal attention to his health, yet had enormous energy and appetite for work. In 1830, the Massachusetts legislature and Governor Lincoln, a former Amherst College trustee, appointed him to conduct a geological survey of the state, specifying that expertise in astronomy and trigonometrical surveying were required for the position. The job was tailored to his skills, and Edward considered outdoor activity the best antidote to poor health.

He trekked up every mountain, down every gorge, around lakes and across meadow and marsh for an estimated 10,000 miles. He oversaw his assistants, but the overall design and writing of the work were his. In the end, he made three complete collections of rock specimens, one for himself, one for Amherst College, and one for the state.

Orra sometimes accompanied him to sketch landscapes for inclusion in the report. Women often published anonymously (like "Miss M______" who also made some of the drawings but was too shy to have her name in print), but Orra took credit for her work, although as "Mrs. Hitchcock," not "Orra White Hitchcock." She was not paid. Nor were Miss M______ and a student who contributed several drawings.

Edward was happy to have the company of family on these trips and thought the travel good for Orra. It is not recorded whether they left the children in the care of the boarders or took them along, but son Edward later reminisced that when he was old enough, he loved to go with his father on field work. Ever frugal, they ate bread and cheese for dinner and slept under the stars at night.

The first edition of the Report on the geology, mineralogy, botany and zoology of Massachusetts was published in 1832-33. The first major section, "Economical Geology," covered practical questions regarding useful materials. "Scientific Geology" addressed classification and other research questions, and "Elementary Geology" was a primer for readers unfamiliar with the subject. The most unusual for a scientific report, "Scenographical Geology," was meant to arouse pride in the state's natural beauty. This is the section that was embellished with Orra's landscapes. It also included quotations of such poets as the famous William Wordsworth and an American named John Brainard, as if to assert that an American's poetry could be just as fine as an Englishman's.

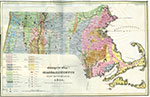

Hitchcock was busy with more surveying and several printings and revisions of the report during the 1830s. A second edition that included an atlas was issued in 1835. By the time the Final Report was published in 1841, eighteen other states were conducting their own similar surveys. The 1841 edition had significantly more material on soils and a long section on the fossil footprints that Hitchcock had begun studying in 1835.

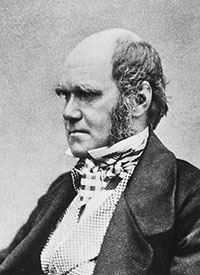

The report was distributed to government offices, towns, colleges, and schools in New England and to men of importance in Britain and Europe. Charles Darwin, long before he became famous for his theory of evolution, wrote in a letter of thanks that he was especially interested in the material on alluvium (in reference to glacial theories) and assured Edward that his name "was certain to go down to long future posterity" for his work on fossil footprints.

Orra White Hitchcock's Landscapes

Orra White Hitchcock's Landscapes

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

A Geological Map of Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock

A Geological Map of Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock

Edward Hitchcock's Saddle Bags

Edward Hitchcock's Saddle Bags

Edward Hitchcock's Chemical Field Kit

Edward Hitchcock's Chemical Field Kit

Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock

Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts, Edward Hitchcock

Edward Hitchcock's Letter to Thomas Greene, September 29, 1831

Edward Hitchcock's Letter to Thomas Greene, September 29, 1831

Charles Darwin's Letter to Edward Hitchcock, November 6, 1845

Charles Darwin's Letter to Edward Hitchcock, November 6, 1845

Edward Hitchcock's Surveying Compass and Stand

Edward Hitchcock's Surveying Compass and Stand

The Feminine Role in Coloring Maps

The Feminine Role in Coloring Maps

The Rise of Geology in the Early 19th Century

The Rise of Geology in the Early 19th Century