MENU

MENU

MENU

MENU

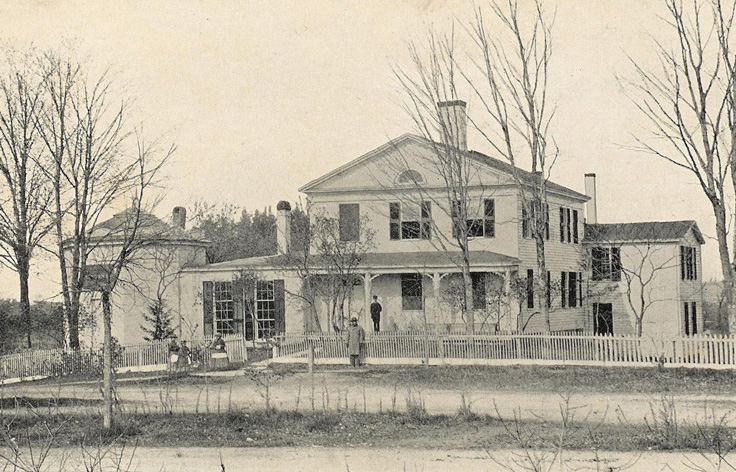

The Hitchcocks' home in Amherst, where they lived before and after his term as president. The octagonal room, added in the late 1830s, preceded by about a decade the Octagon that housed the Woods Cabinet. Image courtesy of Buildings and Grounds Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College.

Despite a burgeoning intellectual life and stimulating visitors, all was not well in early 1840s Amherst. The college was in financial trouble. Enrollment was down from 259 students in the 1836-37 school year to 118 in 1845. The college was in debt, had no endowment, and could not obtain further grants from the state. Bankruptcy was a real possibility.

In despair, the president, Heman Humphrey, offered to resign and a search began for his replacement. Things were looking grim when the faculty proposed an idea: they would forgo salaries and instead divide the remainder of income after school expenses among themselves, if the trustees would elevate Edward Hitchcock to the presidency.

Edward was hesitant. Acutely aware of appearances, he was afraid it might embarrass the college to have a president who lacked a college degree. On the other hand, he knew his strengths, one of which was a sure sense of economy, and he had the trust of the faculty and students. Perhaps this was what God meant for him to do. He accepted and officially became president on April 14, 1845.

Reluctantly, he moved the family into the President’s House. Even though it was just down the street, he missed his own home, which by comparison felt secluded from the campus. He continued to lecture students and listen to their "recitations," because he enjoyed it and didn't want to become distant from them. He still led morning prayers and was deeply involved in religious revival and prayer meetings, met regularly with trustees, faculty, and the Prudential Committee (finance), and answered 400-500 letters annually. He applied himself conscientiously to every task, whether or not he enjoyed it. It was a heavy load, but Edward Hitchcock relished precisely such challenges.

The faculty's willingness to put their financial lives on the line, combined with Edward's reputation for financial probity, inspired confidence in men who had substantial funds to donate to the college. (Edward's salary had been reduced from his professorial pay of $700 to $550 per year and the faculty's to $450 each.) By the time Hitchcock stepped down from the office in July of 1854, the college was no longer in debt and had instead a sizable student body and four new endowed professorships. A new building, the Octagon, had opened in 1848, housing an astronomical observatory and the Woods Cabinet of geological collections. A library was constructed in 1852 and opened in 1853.

A particularly gratifying surprise was announced at his retirement from the presidency. A hope he had given up on, a cabinet to permanently exhibit his ichnological collection, would be built with funds from the estate of Samuel Appleton. The next year, the Appleton Cabinet was constructed to display Hitchcock's fossils and two other donated collections, the Gilbert Museum of Indian Relics (from his son Edward) and the Adams Zoological Museum (from the estate of Professor Charles Adams).

Plucky little Amherst College had not fallen but shown its character, and it was taking its place among the leading colleges of New England.